Something out of the ordinary happened to me yesterday. It started as one out of the ordinary thing, and by the end was out of the ordinary for an entirely different reason. It started as my partner and I finished putting the groceries away. We put everything away. And moments later, the refrigerator starting making its two-tone alarm beep like when the door hasn’t been closed all the way. I check the fridge and freezer door. They’re closed. And so begins the adventure.

I’m not going to give you a blow-by-blow account of what happened. But I will give bits and pieces as they relate to how we approached the issue. In essence, my partner and I fixed our fridge with the scientific method, so I will describe the general shape of how it went down.

Inception, and the first hypothesis

It started, as science often does, with something off-the-wall and not particularly scientific. In our case, my partner pushing some buttons, not being able to get the beeping to stop, and then say, “Well, get ready to go shopping for a new fridge.” After a little while, though, the proper process got underway. We started with a review of the literature. In particular, he dug out the owner’s manual to see if it had a troubleshooting guide and I went to the Internet to see if I could find a repair place. In both cases, the results suggested more research was necessary. The owner’s manual was next to useless. The worst problem it tried to help diagnose was frost on your food…in the freezer. And the only repair place certified to repair our unit was closed until Tuesday because of the holiday weekend.

We did some preliminary observations and realized that not only was it continuing to beep, but the internal temperature indicator said the fridge temperature was beginning to rise (though the freezer’s wasn’t). Initial hypothesis: the compressor was dead. Then more data came in that brought that hypothesis into question: the fridge light wasn’t coming on. Since we didn’t think the compressor going out would affect the fridge light (the freezer light worked fine), and because we found there was only one compressor, the hypothesis that it was the compressor no longer fit all the observations.

Another hypothesis

New hypothesis: The circuit board had died, or maybe some faulty wiring. Time to bring in some experts in a related field. My father was an electrical engineer, so I called him and explained the problem. He gave us a new idea: probably a relay that controls the flow of cold air from the freezer into the fridge. But oops, that doesn’t work because we have a bottom-freezer model, and we’ve pulled the fridge apart far enough to realize there’s a separate cooling coil in the fridge from the freezer—therefore, the unit isn’t set up like the ones he had experience with as an electrician. So, appeal to authority has failed.

In Dad’s defense, it was over the phone, so he couldn’t actually look at anything; I had to describe it, and I am no electrician. He did offer a number of other suggestions, but as chance would have it, none of them were the right answer. One suggestion he made was to diagnose the door switch. I told him it couldn’t be that because we’d already thought of it: the alarm was (still!) beeping, which was what it did when the door was stuck open, but the light was off, which is what it did when the door was closed. It couldn’t be both.

Research and Observation

We did another “search of the literature”. This time my partner found not just the owner’s manual but the service manual. Only $12 for the electronic version! Woo hoo! (Oh…never mind. It’s electronic but they ship it to you on a USB drive in the mail. And it’s a long weekend.) He says, “The Internet isn’t pulling its own weight in this.”

More observation. He says every time he looks in the fridge, it feels colder than the temperature indicator on the outside. Hmmm. Measurement: put a thermometer in the fridge. Aha! Digital indicator on the outside says it’s 66F inside, but our thermometer says 40F at the bottom of the fridge and 60F at the top. New hypothesis: the temperature sensor has gone out.

We do some research on what a sensor would cost. Uh oh. There are 3 different temperature sensors in the fridge section. We don’t know which one might be the problem. But we notice the one with the yellow wire causes a little layer of frost to appear on the fridge coils when it’s plugged in, but they defrost almost immediately when it’s unplugged. That one must be working.

Headway! We find some obscure research (also known as a free PDF version of the service manual) online. Unfortunately, it was clearly written by people whose native language wasn’t English. “Touch button type (ding-dong sound) there is “ding-dong” sound to confirm input periodically for each one second for button operation in each control panel.” That’s how we turn off the beeping (it’s now been beeping for nearly 4 hours…turning that off was becoming a higher priority than getting the fridge cold…) We notice that certain combination of button presses set the fridge into different modes. New hypothesis: we accidentally bumped the buttons and put the damned thing into some kind of “incessant beeping mode.” He goes to see if he can put it into self-test mode and collect data on what components are working (like the sensor?) while I read more.

A glimmer of hope, a revival of the dead

Ah, but a clue! I notice that it has a “Sabbath function” that “is used only in special area.” When in that mode, the fridge light stays off even when the fridge door is open. Hmmm. More reading. Then this intriguing/infuriating line: “Alarm begins after 2 minutes when the door is open and runs in every 2 minutes. If the door is not closed properly, MICOM will indicate that the door is open, and alarm continues. If the alam goes for 10 minutes, the light in the compartment will be off and not be on in the situation that the door opens.”

Aha! Back comes an old, discarded hypothesis. It’s possible that it is the door switch. That idea had been eliminated because if the door was stuck open, the light should be on. But if the service manual says the light will shut off automatically after 10 minutes of the door being open, then this hypothesis now actually fits the observations better than if a temperature sensor was going haywire.

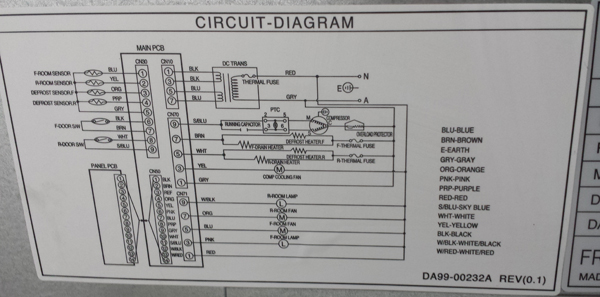

My partner pulls out his multimeter and gets access to the circuit board. I look up which contacts correspond to the door switches. We verify that the freezer door is actually closed, and that the meter readings match that status. Then we look at the fridge door. Eureka! Even though the door is actually closed, the electrical readings look like it would if it was open. Everything is beginning to make sense. We review all of our observations we’ve made so far and compare them to our now-frontrunner hypothesis. It all fits except maybe for the fact that our thermometer says a different temperature inside than the digital display. But we figure that might be because the circulation fan shuts off when the door is “open” and perhaps the cold air isn’t getting to the sense (which had led us to the “haywire sensor” hypothesis).

My partner pops out the switch. We test that end of the wires. Same results. Almost immediately the compressor comes on. The fan begins circulating air in the fridge. The air is decidedly cold. We close it all up. The digital temperature indicator on the door starts creeping downward and before long is at normal fridge temperature. Woo hoo! (Later, he pulled apart the switch and found that a 0.15 gram strip of copper had lost its bounce and had essentially locked in the “door open” position.)

Science is messy, but it works

Some things to notice about the process:

- Over the course of the whole process, we went through multiple hypotheses

- One of the ones that got discarded was the correct one

- The right one got discarded because of an erroneous assumption

- That erroneous assumption was corrected by information gathered outside of the present “experiment” (in other words, you save yourself a headache if you first have an idea of what other people have learned about this situation)

- It was a very messy process where observation, hypothesis formation, analysis, and experimentation all kind of smeared into one another

- Everything was very logical (except maybe our shift in desire from fixing the fridge to just wanting to turn off the beeps). The only time intuition came into it was in trying to come up with new hypotheses that better fit the observed facts. And that intuition was wrong more than it was right. Remember that his first intuitive flash was that it was the compressor, and mine was that it was the circuit board.

- All of the above resulted in the right answer. Despite it being a messy process, and the erroneous dismissal of the right answer, sticking to the scientific method eventually brought us back to the solution.

In the end, we found a new switch for $6. A new fridge of similar size would have been about $400-500. So science saved us at least $394! And made us feel grateful for silence, and for cold milk and deli meat. And gave us something that was a surprisingly intense intellectual challenge. Thanks, science!